Contributing Code

Every state presents unique challenges when it comes to data. Some results will require manual clean-up or data entry, steps that are hard to capture in code. Others will be perfectly structured CSVs, ready for any mere mortal to download and use.

Whether you’re facing a Sisyphean challenge or handling the friendliest of data, the OpenElections team will work with you to bring raw results into our world (a much cleaner, saner world, we hope!).

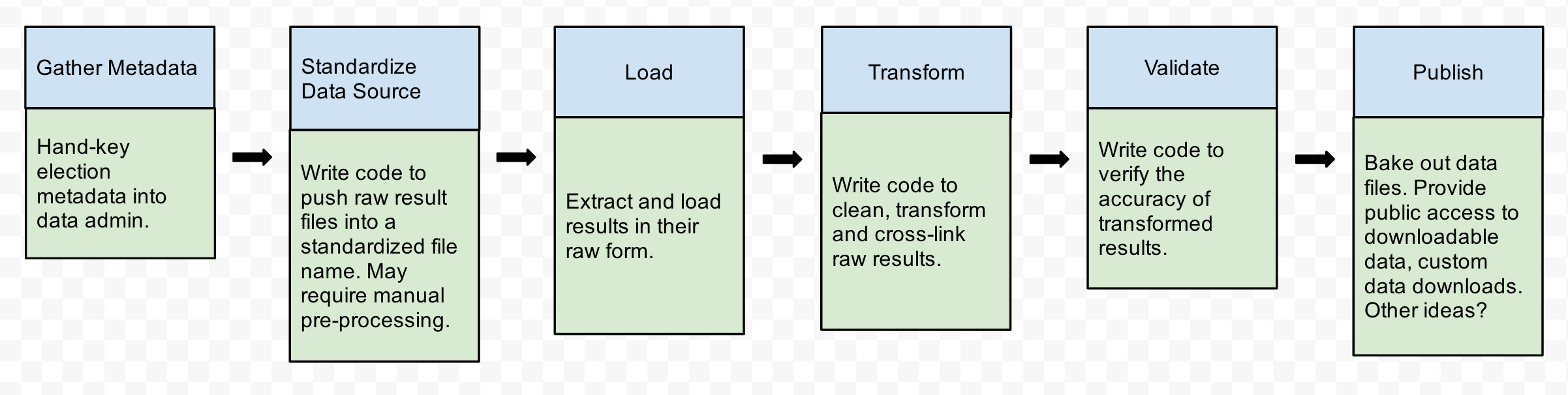

At the 30,000 foot level, here’s what our “world” looks like:

- Acquire raw results data from the state using the metadata we’ve gathered.

- Standardize the name of raw data files.

- Load raw data into our backend data store (Mongo, if you’re wondering).

- Transform raw results data in a step-by-step fashion, for example, by parsing names into separate fields or standardizing party and office names.

- Verify the accuracy of the transformed results data.

- Bake out structured, easy-to-use CSV and JSON files that form our public API.

We use Python (2.7 for now) to accomplish most of these tasks.

Here’s a high-level snapshot of how a state directory’s code is organized, using Maryland as an example:

openelex/us/md/process.md- Markdown-formatted description of non-standard data gathering process, if not fully automated.corrections.csv- CSV containing info on corrections to be applied to raw results.datasource.py- maps raw data sources to standardized filenames and metadatamappings/- misc metadata files for data processing pipelineload/- load.py - data loaders from local cache into mongoparse/- (optional) break out parsers if you have lots of themtransform/- transform.py - step-wise data clean upsvalidate/- validate.py - data integrity testsbake/- bake.py

As a contributor, we appreciate any part of the data process you can help us with. Let’s dive in!

Bootstrapping

Before you can do any coding, you have to bootstrap your environment. Once that’s done, you’re ready to start feeding data into our pipeline.

Data Pipeline

Overview

OpenElections provides a management command, openelex, to manage the data processing pipeline. You don’t have to write any subcommands of your own, but you can use the management command to make local development easier and help us process the data you’ve gathered.

openelex provides command-line tasks to:

- Inspect data source urls and associated metadata

- Download raw data and save it locally under a standardized file name

- Inspect and clear files downloaded to a local cache

- Load data from cache into the data store

- Apply transformations to stored data

- Run validations to ensure data integrity

- Bake standardized results out to CSVs and JSON

The OpenElections team will help you wire up your code so that it “just works” using the framework.

Here’s a quick primer on how to get started.

Pre-flight check:

- Have you bootstrapped your environment?

You can learn more about available subcommands by dropping to the command line:

$ openelex --helpView help for a specific task.

$ openelex cache.clear --helpDatasource

Our data processing pipeline starts with datasource.py, which handles the process of taking source files and organizing them for our system. This module encapsulates all the information needed to download data files from source agencies, save the files locally under a standardized name, and make them available for parsing and loading into our data store.

Like the other parts of the process, a state-specific datasource.py subclasses a BaseDatasource that includes some generic functions for the most common tasks. Inside the state-specific datasource.py you’ll write functions that handle parts of the process particular to that state: setting up scrapers, handling unusual file paths or a mix of formats.

Most states involve more than a simple web scrape. You might have one big database dump for all election years, or unparseable PDFs that require outsourcing to Mechanical Turk for data entry. More likely, you have a combination of easy-to-use data and older files that are harder to work with. For example, some West Virginia results are stored in PDF files; we convert them to CSV files that match our naming conventions. Whatever the case, the OpenElections team will work with you to come up with a solution that feeds into our data pipeline. It can be a heavy lift, but once complete, the datasource.py step makes downstream processing much easier.

A lot depends on how the results data is organized and stored by the original source. It may come as single spreadsheet files, individual HTML pages or PDF documents. The job for the datasource file is to provide an interface to that data, rename the files using OpenElections conventions and provide some basic political geographic elements. For example, here is the representation of a single results file from Baltimore City for the 2012 primary, mapping it to a OpenElections generated filename:

{

"ocd_id": "ocd-division/country:us/state:md/place:baltimore",

"election": "md-2012-04-03-primary",

"raw_url": "http://www.elections.state.md.us/elections/2012/election_data/Baltimore_City_By_Precinct_Republican_2012_Primary.csv",

"generated_name": "20120403__md__republican__primary__baltimore_city__precinct.csv",

"name": "Baltimore City"

}Ideally, the generated files correspond directly to the original source files so that even if the original file is a PDF and the generated file CSV, they both cover the same contests and results. In the case of most PDFs, the generated_name will be a CSV file.

The best-case scenario is that all election results data for a state is available in the same file format, which means that you’d likely only need a small handful of functions to create the mappings. At the other end of the spectrum are states that use a combination of formats and naming conventions over time.

To help construct these mappings, you should store helper files in a {state}/mappings directory. The first is {state}.csv, which lists political jurisdictions (usually counties, but can also include cities and other types of divisions that are reporting levels) and connects them to the OCD_ID. In states where it is necessary to directly map URLs to generated_name, a url_paths.csv file can be used (see Ohio for an example).

The Python API documentation can tell you which methods need to be implemented in your state’s Datasource class as well as the utility methods available to help implement the class. There is also an example class implementation for a simple case.

Once you’ve crafted datasource.py, you can query it for information about a state’s data sources from the command line.

NOTE: Below code snippets use Maryland as an example.

List election metadata for all years (from our Metadata API; warning: output is very verbose).

$ openelex datasource.elections --state mdList metadata for one year.

$ openelex datasource.elections --state md --datefilter 2012List urls for raw data sources.

$ openelex datasource.target_urls --state md --datefilter 2012List the mapping between raw data source urls and standardized file names (saved to the local cache).

List all years.

$ openelex datasource.filename_url_pairs --state mdList one year.

$ openelex datasource.filename_url_pairs --state md --datefilter 2012And most importantly, the datasource.mappings task provides a year-by-year breakdown of metadata (raw url, standardized file name, OCD ID, and election ID). These bits of metadata are critical to the subsequent data loading step. The OCD_ID is a standardized way to refer to specific political geographies (states, counties, congressional districts, etc.) that makes it easier for OpenElections data to be shared across projects.

List all mappings for state.

$ openelex datasource.mappings --state mdList mappings for one year.

$ openelex datasource.mappings --state md --datefilter 2012Fetch/Cache

The datasource.py file sets up the basic process, but it doesn’t actually grab the raw result files. That’s the job of fetch.py. You can use the fetch task to download raw result files for your state all at once, or year by year. Downloaded files are stored under their standardized names in a {state}/cache directory (e.g. md/cache). An important point: the {state}/cache directory is excluded from version control.

We use the useful requests library to make HTTP requests and BeautifulSoup for HTML parsing.

Download all files for the state.

$ openelex fetch --state mdDownload files for one year.

$ openelex fetch --state md --datefilter 2012List the contents of your local cache.

$ openelex cache.files --state mdList cached files for one year.

$ openelex cache.files --state md --datefilter 2012Load

The load.py file is responsible for taking the raw results and putting them into a MongoDB database. The goal is to keep the data loader simple, and defer any data cleaning and transformations to downstream steps in the process. The loader should create RawResult model instances whose fields closely reflect the values in the raw data files. You should do only minimal processing of the data in the load step, such as stripping leading and trailing whitespace or converting strings representing numeric values to numeric data types.

States may have results data that exceeds the minimum attributes in our Results spec; that information should be loaded as dynamic attributes on the RawResult model instance using whatever Python object best fits the data. For example, if a state includes the gender of the candidate, you would add a slugified version of the original column (in this case, ‘Gender’ becomes ‘gender’) and then the value. If the original column is not obvious - if it is something like ‘CND_GND’, for example - then give the attribute a readable name like ‘gender’ and document this change in a comment where the attribute is assigned.

To implement the loader for your state, you’ll need to implement a LoadResults class in the openelex.us.{state}.load module. In most cases, this class should be a subclass of openelex.base.load.BaseLoader and you’ll need to implement the load() method.

Depending on the complexity of a state’s data - for example, if different years come in different formats or contain different types of data - the load.py could contain multiple classes and helper functions to handle this process. In this case, LoadResults.run() will delegate to the other loader class’ run methods. openelex.us.md.LoadResults is an example of using this pattern.

We use unicodecsv to read CSV files.

Once you’ve implemented the load module for your state, the load task imports raw results from locally cached files into the data store.

Load all raw results from files in local cache to the database.

$ openelex load.run --state mdLoad results for one year.

$ openelex load.run --state md --datefilter 2012Transform

Transforms create clean records or update data after they’ve been loaded into our data store. The transform step is where you’ll place results data that you loaded into RawResult models, into our defined models, including Candidate, Result and Contest. Transforms also clean or extract values from the raw data. A typical update might be parsing candidate names from a single field into name components.

Transforms must be defined and registered in a {state}/transforms.py file. Simple transforms can be implemented as functions, but more complex transforms are better implemented as a class. To implement a class-based transform, create a class that is a subclass of openelex.base.transform.Transform, declare a name attribute and implement the __call__ method.

from openelex.base.transform import Transform

class CreateCandidates(Transform):

name = 'create_candidates'

def __call__(self):

# ...Transforms are run in the order that they are registered, so ORDERING IS IMPORTANT.

from openelex.base.transform import registry, Transform

def some_transform():

# ...

def another_transform():

# ...

class ClassBasedTransform(Transform):

# ...

registry.register('md', some_transform)

registry.register('md', another_transform)

registry.register('md', ClassBasedTransform)Also note that you can register validators with a transform. Validators, covered in the next section, are functions that check data after a transformation to ensure the result is correct.

from openelex.base.transform import registry

from openelex.us.md.validate import validate_something

def some_transform():

# ...

registry.register('md', some_transform, [validate_something])Once you’ve implemented and registered transforms for your state, the transform task is used to list and run the transforms.

List available transforms for state.

$ openelex transform.list --state mdMD transforms, in order of execution:

- parse_candidate_names

- standardize_office_names

You can select one or more transforms to run using the –include flag with a comma-separated list of function names. Or you can run all but selected transforms using the –exclude flag.

Run all transforms for state.

$ openelex transform.run --state mdOnly run name parsing transform.

$ openelex transform.run --state md --include parse_candidate_namesRun all transforms except name parsing.

$ openelex transform.run --state md --exclude parse_candidte_namesValidate

Validations help ensure data integrity by running queries against results in the data store, typically after a particular transformation is run (You can link one or more validators with a transformation; see the previous section). They exist in a {state}/validate.py file.

All validations should be functions prefixed with “validate_” and importable from openelex.us.state.validate (e.g. from openelex.us.md.validate import validate_unique_contests).

Similar to transformations, you can include/exclude validations.

List available validations.

$ openelex validate.list --state mdRun all validations for a state.

$ openelex validate.run --state mdOnly run validate_unique_contests.

$ openelex validate.run --state md --include validate_unique_contestsRun all validations except for validate_unique_contests.

$ openelex validate.run --state md --exclude validate_unique_contestsBake

This is the long-awaited final step, where we bake out raw results after applying transforms (and validations, of course!) into flat files using one or more user-friendly formats. Regardless of format, results should conform to our standardized results spec.

You’ll most likely want to use the bake.election_file command to export results with one file for each reporting level in an election. You can also use bake.state_file if you want to bake a single file with all of a state’s results or all of a state’s results for a single year rather than per-election.

Both commands take these parameters:

state- Required. Abbreviation of the state whose results you want to export.fmt- Format of exported results. The value can be eithercsv(the default) orjson.electiontype- Only export results from elections of this type. Value can beprimaryorgeneral. The default is to export results from all types of elections.raw- If set, export raw results instead of transformed results. Raw results have a standard schema but have unprocessed values straight from the raw data files. Default is to bake transformed results.outputdir- The directory where result files will be created. This defaults to theus/bakerysubdirectory.level- Only export results for this reporting level. The default is to export results for all reporting levels.datefilter- Only export results from elections from a certain day or year. This value must be specified in ‘YYYY’ or ‘YYYY-MM-DD’ format. The default is to export results from all elections.

Export results for a state with one file for each reporting level in an election. This is the command used to generate the downloadable results that we publish.

$ openelex bake.election_file --state mdExport county-level results for Maryland’s 2012 general election election.

$ openelex bake.election_file --state md --datefilter '2012-11-06' --level countyExport all results for a state into a single file.

$ openelex bake.state_file --state mdExport results for one year.

$ openelex bake.state_file --state md --datefilter 2012Export results to a specific directory. The default is OPENELEX_ROOT/us/bakery/.

$ openelex bake.state_file --state md --datefilter 2012 --outputdir ~/data/Export results to a JSON file instead of CSV.

$ openelex bake.state_file --state md --datefilter 2012 --format jsonPublish

This step is only relevent to core contributors with write permissions to repositories in the openelections organization on GitHub.

Before you publish results:

- Create a personal access token that will be used to authenticate to GitHub.

- Set the

GITHUB_USERNAMEandGITHUB_ACCESS_TOKENvariables in your settings module. - Create a repository named

openelections-results-STATE_ABBREVto store the results for this state.

Publish transformed results for Maryland.

$ openelex publish --state md --datefilter 2012 --format jsonPublish raw results for Maryland.

$ openelex publish --state md --rawPublish raw results for 2012 Maryland elections.

$ openelex publish --state md --raw --datefilter 2012Manual Processes

Data extraction

Some data sources are just too unwieldy to parse using a fully automated process. Think landscape-oriented, image PDFs with angled header columns and 8-point font. In such cases, hand-keying data will be the only option, or perhaps a combination of hand-keying and an automated process such as Tabula.

Any data extraction process that is not fully automated (and integrated into the data processing pipeline) should be documented in a process.md file. The description should be minimal, just enough info to help recreate your process. Think bullet-points for the uninitiated.

If a state requires a manual process, that process is documented in {state}/process.md, along with any particular issues you might have come across during the process. These may include results that are incomplete or missing, or results which may require further investigation/follow-up with the source agency.

Populating url_paths.csv

States with results that require pre-processing (usually conversion from a PDF to a csv file) or other non-standard processing such as scraping single pages should have a url_paths.csv file in the core/openelex/us/<state>/mappings directory. Such files help to connect raw files like PDFs to their processed CSV versions, which are stored in state-specific repositories on GitHub (see West Virginia as an example). As such url_paths.csv files contain the following attributes:

- date (of election, value should be formatted in the format yyyy-mm-dd)

- office (a slugified version of the office name, such as

state_senateorgovernor) - district

- race_type

- party (for primary elections)

- special (boolean flag, value should be formatted as the string “true”)

- path (the path from the raw file URI - a full URI is acceptable if the hosts differ)

- data_url (optional; the url to the processed CSV in the GitHub repository - it should begin with https://raw.githubusercontent.com/)

The data_url attribute is optional if the files are HTML files that will be scraped and stored as part of the load process. The datasource.py file will use the url paths to identify the results files for ingestion. If the state you are working on has PDF results files or multiple systems for handling/publishing results in several formats, you’ll need a url_paths.csv file.

You can see example files for West Virginia and Ohio.

Populating {state_abbrev}.csv

The file us/{state_abbrev}/mappings/{state_abbrev}.csv can be edited to contain the names and Open Civic Data identifiers for a state’s different jurisdictions/electoral geographies. The most common case is the list of counties. You may need to iterate over the list of counties to build URLs for per-county results files.

This shell command will populate the CSV file with county names and OCD IDs. Be sure to change the value of STATE_ABBREV to your state’s abbreviation. This example uses Washington (wa).

export STATE_ABBREV=wa

wget -qO- https://raw.githubusercontent.com/opencivicdata/ocd-division-ids/master/identifiers/country-us.csv | csvgrep -c id -r "ocd-division/country:us/state:$STATE_ABBREV/county:[^/]*$" | csvcut -c id,name,census_geoid |sed -e "1 s/census_geoid/fips/" | sed -e "1 s/id/ocd_id/" | sed -e "s/ County,/,/" | sed -e "s/place-//" > us/$STATE_ABBREV/mappings/$STATE_ABBREV.csvCorrections

You’ll occasionally run into raw result files that contain incorrect data – a candidate name misspelled, or candidate parties swapped. Ideally, such inaccuracies should be reported to the source agency so they can fix their data. Of course, to ensure accuracy in the meantime, a record of the correction should be stored a corrections.csv file so that during the Transform process the raw data can be fixed.

This file should live at at the root of the state directory (core/openelex/us/<state>/corrections.csv) and contain four columns:

- source - standardized name of raw results file that has incorrect data. From Datasource.

- description - Description of error and change that is necessary

-

fixed? - [true false] - transform - Name of transform that applies correction. Blank until transform is written.

Metadata

Metadata for offices and parties are loaded from the CSV files us/fixtures/office.csv and us/fixtures/party.csv.

As you encounter new offices or political parties in your state data, you should add them to these files.

The updated data can be loaded into the database using the load_metadata.run task. For example, to load new offices, use the command:

$ openelex load_metadata.run --collection=officeEn Fin

Time to celebrate! You’ve helped bring transparency to American democracy! And in the process, you got a sweet OpenElections T-shirt that proves to the world you helped FREE THE DATA! (You did get a shirt, right?)

But really, we owe you a hearty thanks, whichever part of this process you pitched in on. Our “modest” goal is to bring some sanity to U.S. election results, and there’s always more work to be done.

We welcome your ideas on new ways to add value and generally make the raw output of democracy more accessible to all.

The OpenElections Crew